Exploring the Cultural and Visual Storytelling of Puppetry

A Cultural Observation and Museum Field Research Study

Bree Jordan | Summer 2025

Project Goals and Background Research

“How is human culture and society expressed through the visual storytelling of puppetry, and how can we examine its cultural significance through exhibits curated both in person and online?”

When I first started this project at the beginning of the summer, I fully intended for it to be an opportunity to do a paper on one of my favorite museums, the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia. But while researching more about the objects curated within the museum, I realized that I wanted to learn more about the cultural ties behind puppetry and its role in storytelling within each culture. Anthropology is the story of humanity, and I think storytelling goes hand in hand with what it means to be human. To quote anthropologist Ed Bruner, “Our anthropological productions are our stories about their stories; we are interpreting the people as they are interpreting themselves.” Puppetry isn’t just a form of entertainment for children, it is a profound form of cultural expression, with an understanding of the world that extends far beyond the stage; exploring complex topics of history, identity, morality, spirituality, and imagination, as well as the storyteller’s role in the puppeteer, giving life to the performance and puppet.

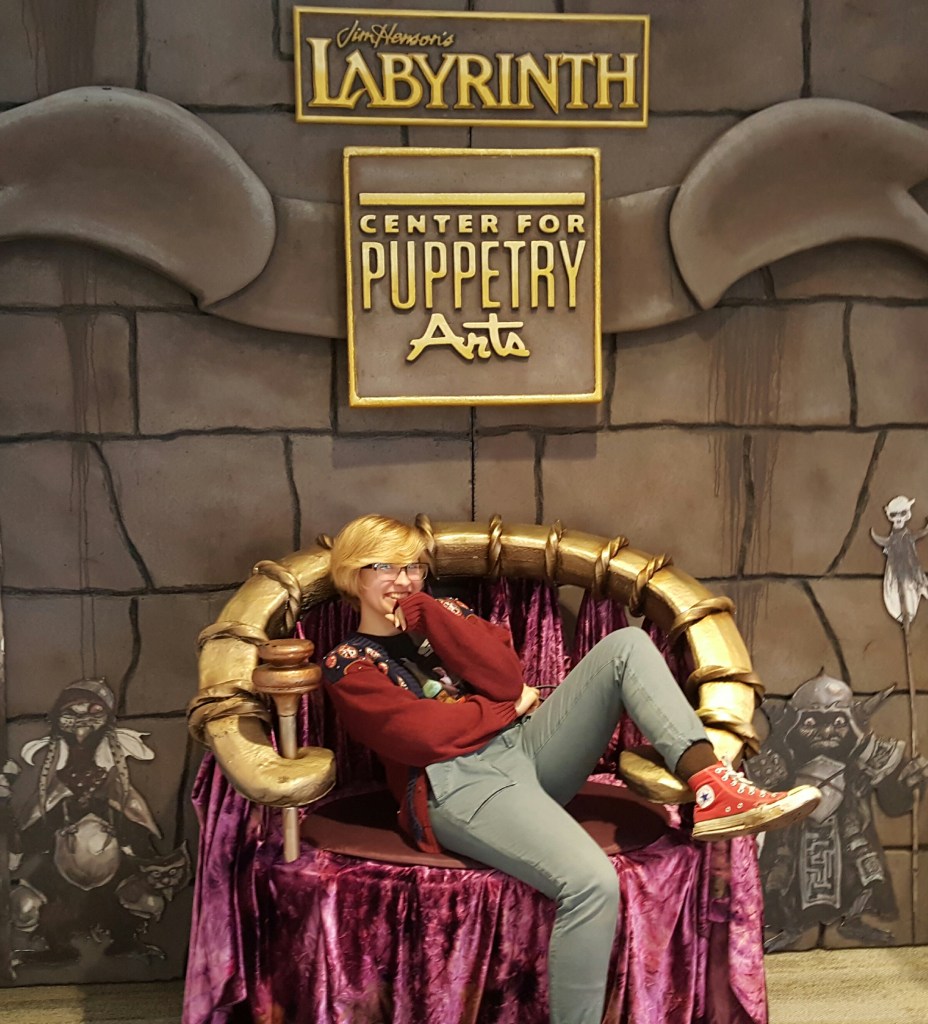

I love museums and have decided to go back to college after 10 years to pursue a degree in Anthropology and Archaeology, with the hopes of working in museums and education. The Center for Puppetry Arts is a museum I have held near and dear for many years: My very first visit was in 2016 with my dad to see “Jim Henson’s Labyrinth: Journey to Goblin City,” a special exhibit they hosted for the 30th anniversary of my favorite movie, Labyrinth. I was deeply impressed with the collection and the museum itself, and it was a very special experience getting to visit with my dad. Puppets have always been a big part of my life: from Fraggle Rock and The Muppets to Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and Between the Lions. Puppets offered a tangible and playful way for me to explore topics in a creative and engaging way, and I loved it as a medium of storytelling.

Around the world, puppets are used in religious rituals, political protest, street theatre, and children’s education. In places like Indonesia, Turkey, Nigeria, Iran and Japan, puppetry is deeply tied to myth and community. These connections are visible not just in performance but in how the puppets are even made: from the materials, construction techniques, and gestures used to animate the puppets. Understanding these cultural ties through cultural relativism allows us to see each puppetry tradition as a unique window into the worldview of its community, and museums offer a great opportunity to educate and help people expand their worldview to learn more about other cultures.

In conducting my research, I decided to read a few different books and articles from different anthropological sources:

Teri J. Silvio’s Puppets, Gods, and Brands: Theorizing the Age of Animation from Taiwan explores the anthropology of puppetry in animation in contemporary Taiwan. Silvio’s work is essential in understanding how puppetry expresses human desire, agency, and cultural narratives across media, especially within spiritual and consumer contexts. Her theory of animation is particularly helpful when thinking about how puppets come to life not only physically but symbolically. Silvio is an Associate Research Fellow at the Institute of Ethnology in Taipei.

Jennifer Goodlander’s Puppets and Cities: Articulating Identities in Southeast Asia situates puppetry as a public performance tied to urban and national identities. Her ethnographic work underscores how puppets become tools for expressing social and political belonging in places like Indonesia and Vietnam, often amid modernization and rapid urban development. She also stresses the connection between puppet movement, urban choreography, and cultural visibility, exploring how puppeteers came together from around the region to create a performance celebrating ASEAN identity. Goodlander is an Associate Professor at IU Bloomington in the Department of Comparative Literature where she teaches classes on Indonesian and global theatre, literature, and other arts.

Sabine Coelsch-Foisner and Lisa Nais, in their book In the Beginning Were Puppets: Towards a Poetics of Puppetry, explore puppetry as a poetic and symbolic form that precedes and exceeds traditional Western theatrical logic. Their study covers puppets from all over the world, the roles and varieties of puppets in these diverse historical, political and cultural contexts, the collection provides new insights into the practices, aesthetics and ethics of puppet theatre, acknowledging the puppet as an expressive object shaped by both human hands and cultural imagination. Their literary and performance-based analysis opens up space for deeper symbolic readings of puppetry across traditions. Coelsch-Foisner is a Professor of English Literature and Cultural Theory at the University of Salzburg, and Nais is a Senior Scientist at the University of Salzburg.

Cariad Astles’ Wood and Waterfall: Puppetry Training and its Anthropology is an article from Performance Research, a scholarly journal of the preforming arts, and offers a reflexive, practice-based account of puppetry training. She emphasizes how embodiment, motion, and tradition create deep knowledge systems that extend beyond the stage. Her work especially highlights the emotional and spiritual connections between puppeteer and puppet, and how this relationship mirrors the broader human experience. Her insights are central to understanding the craft of puppeteering not just as performance, but as transfer of knowledge.

I also read a few articles from Puppetry International, a scholarly journal supported by UNIMA-USA (Union Internationale de la Marionnette). This publication provides a diverse interdisciplinary perspective on puppetry around the world from scholars and puppeteers alike. The mission of Puppetry International is to foster academic and practical scholarship on puppet theatre and related arts as practiced in the past and present around the world and deepen historical and theoretical understanding of the field, and it has been an invaluable resource in both understanding puppetry’s cultural significance and in accessing current conversations in the field. The journal welcomes submissions from scholars and reflective practitioners from all related disciplines. I have a few physical issues of Puppetry International I also purchased while visiting the Center for Puppetry Arts, but also found some digital articles relating to my project.

These sources collectively helped my understanding of puppetry in a cultural light, as well as giving a framework for an anthropological approach to the medium. I also wanted to highlight the key anthropological concepts within this study that helped guide my research and interpretation: cultural relativism, action theory, globalization, and cultural resource management (CRM).

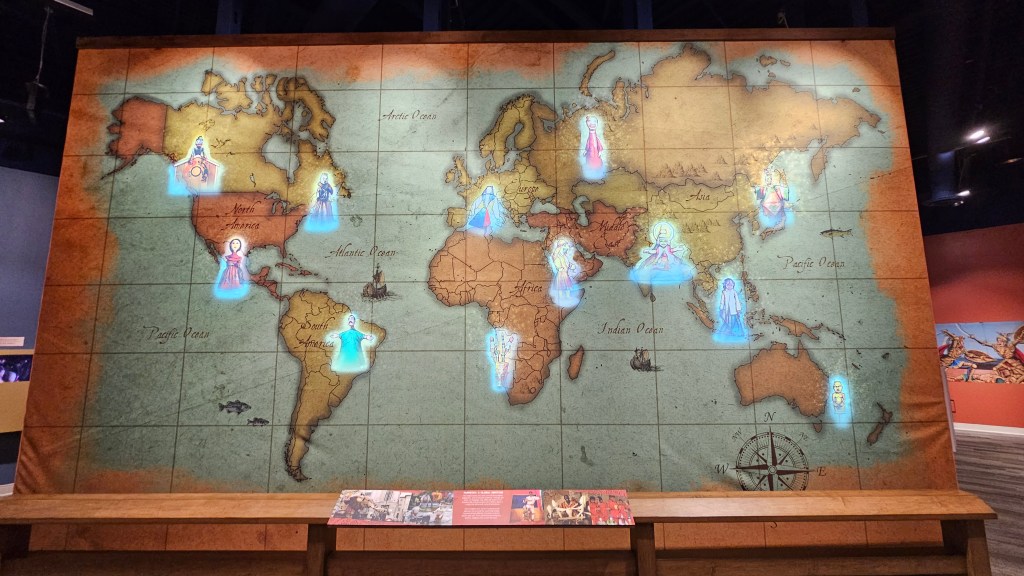

Methodology

I visited the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia on June 13th, 2025, to gather data and photographs from their Worlds of Puppetry Museum. The museum features two main galleries: the Global Gallery and the Jim Henson Gallery. The Global Gallery takes you through different regions of the world, creating a sort of cultural map through puppetry traditions from around the world, while the Jim Henson Gallery celebrates the life and creative legacy of Henson and his impact on modern puppetry. For this project, I focused on the Global Gallery, highlighting international puppetry traditions, cultural narratives, and the global fostering of storytelling and imagination. The exhibit offered a diverse collection of puppets and artifacts, reflecting the storytelling customs and cultural heritage from their region of the world. What stood out the most to me were the interactive elements and thoughtful curation, which helped convey the important role puppetry plays in expressing identity, imagination, and shared cultural values globally.

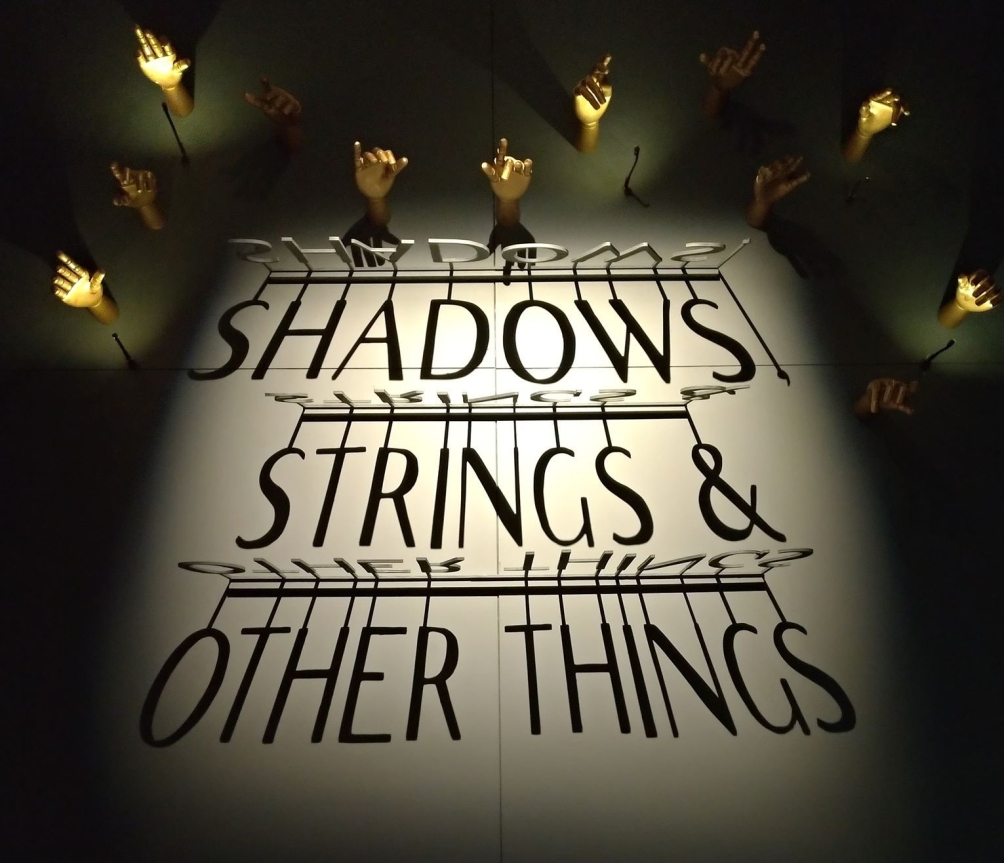

In addition to the Center for Puppetry Arts, I also did a virtual visit of “Shadows, Strings & Other Things: The Enchanting Theatre of Puppets”, which was a temporary exhibition in the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada in 2019.

Although the physical exhibit is closed, there is an amazing digital version of the exhibit that you can virtually walk through, allowing you to see the incredible curation of over 230 puppets from 13 different countries in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. This exhibit explores the art of puppetry and storytelling across world cultures, and also showcases the significance of offering both a physical and digital space for people to experience and foster an interest in puppetry. I highly recommend checking this online exhibit, it was incredibly detailed and informative, and the navigation of the website is very easy. Along with the digital exhibit, I also read through the exhibition catalogue, as well as a curatorial commentary from Puppetry International about the exhibit.

I used ethnographic observation while gathering data at each location to explore the narrative and symbolic functions of the puppets, their cultural origin, and the impact of display context, both physical vs. virtual, on me as a guest in the museum. I tried to be mindful of cultural relativism, attempting to understand each puppetry tradition on its own terms rather than through my own cultural lens. I also tried to evaluate each site on their Cultural Resource Management (CRM), assessing how well the artifacts were preserved, interpreted, and how well they respected the traditions they presented. In both exhibits I found that puppetry was treated not just as entertainment but as an important medium of cultural communication.

Results

Throughout this project, I was reminded that puppetry is a powerful narrative tool that interconnects the people through spirituality, art, social values, and cultural adaptation. Puppetry’s forms vary widely across regions, but what unites them is their capacity to tell stories that reflect the human condition. Both physically in the World Gallery and in the virtual Shadows, Strings & Other Things exhibit, puppetry functioned as a visual storytelling device deeply embedded in local customs, historical memory, and spiritual beliefs.

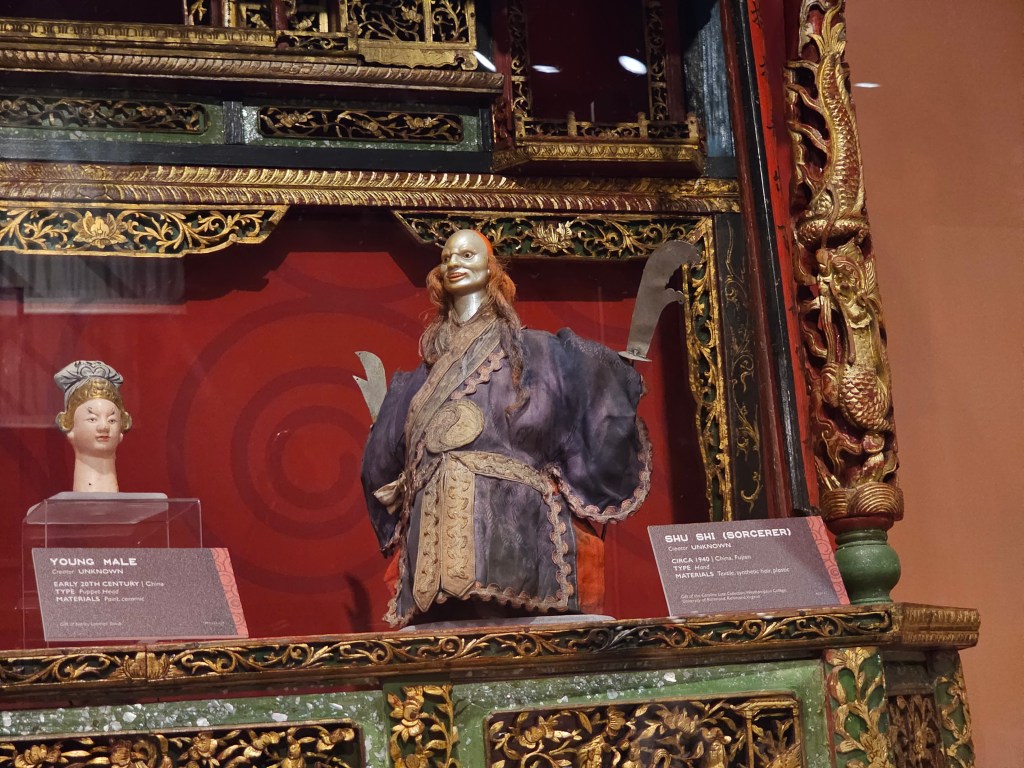

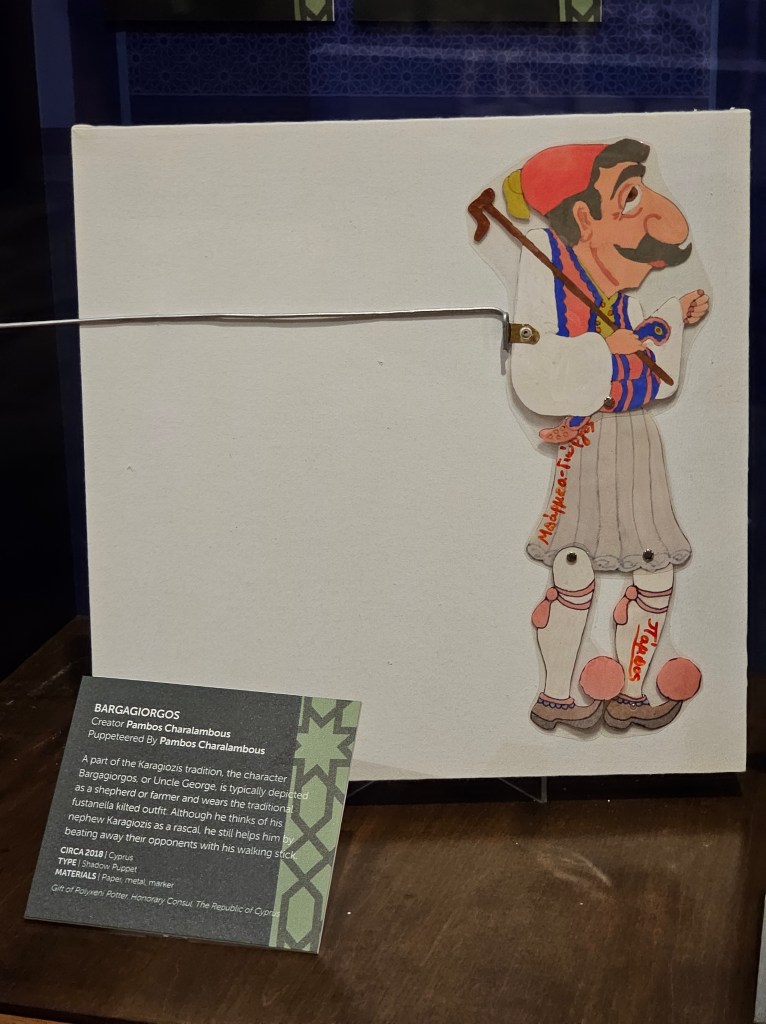

At the Center for Puppetry Arts, Cambodian shadow puppets were displayed alongside South African rod puppets and Sicilian marionettes. Each puppet, whether used in a courtly ceremony or a village performance, told a story that reflected its culture’s society and collective imagination.

Some puppets are used in religious storytelling, like this rod puppet from India. It portrays Ravana, the King of Lanka who kidnaps the princess Sita in the Hindu epic Ramayana, having deep philosophical meanings.

In contrast, the European Punch and Judy puppets illustrated how humor and satire are used to cope with injustice or critique power structures.

These differences highlight the importance of cultural relativism in interpretation: understanding not just the puppet’s form, but its function and how the performers connect with their audience.

The Shadows, Strings & Other Things digital exhibit further illustrated how puppetry engages with issues of modernity and globalization. Online exhibits provide broader exposure but also risk decontextualization. Yet, as seen in both exhibits, communities actively adapt puppetry to remain relevant, fusing ancient techniques with contemporary themes and technologies. The inclusion of contemporary puppets responding to themes such as identity, and digital life showed how traditions evolve while maintaining their roots. For example, the Mamulengo style puppets from Brazil, depicting urban social struggles.

These examples aligned with Silvio’s discussion of animated agency in her book Puppets, Gods, and Brands: Theorizing the Age of Animation from Taiwan as well as Goodlander’s analysis of urban performance in her book Puppets and Cities: Articulating Identities in Southeast Asia, where performance reflects both a yearning for rootedness and a response to modern social fragmentation.

In both exhibits, the puppeteer emerged as a crucial mediator who uses the puppet as an instrument to connect with the audience and convey a character and story. Puppeteers are not merely manipulators; they breathe life into the object, creating presence and intention, allowing the puppet to become a symbol of human emotion, spirit, and conflict. As Cariad Astles states in her article Wood and Waterfall: Puppetry Training and its Anthropology, the training and intuitive connection between puppeteer and puppet expresses emotional, ritual, and embodied knowledge, reinforcing the importance of spirituality and craft in performance. The puppeteer becomes a microcosm of the storyteller, a vital agent in action theory, shaping narratives within specific cultural contexts and historical conditions.

From a museum standpoint, I was really impressed by how both exhibits addressed the ethics of Cultural Resource Management (CRM), especially in the accessibility and resources provided in the Shadows, Strings & Other Things exhibit. Everything reflected an effort to acknowledge and respect each artifact and explain their cultural significance without exoticizing them. This stewardship reinforces the role of museums as educators and protectors of intangible cultural heritage.

Discussion and Conclusion

This project has deepened my understanding of puppetry as both a cultural artifact and a living, performative tradition. Puppets are not just simple objects; they are dynamic symbols animated by human ingenuity, tradition, and creativity. Whether expressing reverence in a religious ceremony or voicing political dissent on a modern protest stage, puppets mirror the societies from which they emerge. Through cultural relativism, I was able to garner a deeper appreciation of the curated puppets by engaging with the beliefs, values, and cultures that helped animate them.

The application of Cultural Resource Management (CRM) within both exhibits helped me assess how puppetry traditions and cultural heritage is preserved, protected, and respectfully displayed in both physical and digital formats. I came away with a greater appreciation for the role of curators, educators, and cultural stewards in ensuring these traditions remain accessible and meaningful to future generations, especially when facing the digital age.

Through action theory, I explored how puppetry connects individual expression with collective cultural meaning. Each performance, each movement of a puppet, is situated in a web of historical, environmental, and social context. These performances allow anthropologists and viewers alike to see the meaning of storytelling behind puppet theatre.

Finally, my exploration of globalization highlights the resilience and adaptability of puppetry. In an interconnected world, traditional puppet forms face challenges like commercialization and homogenization. Yet, they also find new life through global collaboration, digital innovation, and cross-cultural exchange. The traditions persist, evolve, and continue to tell stories that matter across generations and cultures.

In conclusion, this project solidified my belief that storytelling is at the heart of what it means to be human, and that puppetry is an absolutely incredible medium to share and celebrate cultural narratives around the world. For further research, I am interested in conducting a comparative analysis of puppetry across cultures, narrowing my field of study a bit since this was a very broad project that covered many many different areas of the world, as well as exploring the pre-history and history of puppetry as a performative and visual art. I am also interested in looking at puppetry’s role as a tool in education and self expression, seeing firsthand how puppets are used in media with my friends across different industries. Puppetry does not merely reflect culture; it animates it, inviting us all to participate in and carry forward the stories that define us.

Works Cited/References/Acknowledgements

Astles, Cariad. Wood and Waterfall: Puppetry Training and its Anthropology. Performance Research (draft version). Central School of Speech and Drama, https://crco.cssd.ac.uk/id/eprint/4/2/Performance_Research_On_Training_draft_Cariad_Astles.pdf

Coelsch-Foisner, Sabine, and Lisa Nais, editors. In the Beginning Were Puppets: Towards a Poetics of Puppetry. Winter Verlag, 2020. https://www.winter-verlag.de/en/detail/978-3-8253-8623-8/Coelsch_Foisner_ua_Hg_Beginning_were_Puppets_PDF/

Goodlander, Jennifer. Puppets and Cities: Articulating Identities in Southeast Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021. https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/puppets-and-cities-9781350170858/

“Puppetry International.” Puppetry International Research (PIR), UNIMA-USA, https://pirjournal.commons.gc.cuny.edu/

“Puppetry International.” Taylor & Francis Online, https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/rprs20

Silvio, Teri J. Puppets, Gods, and Brands: Theorizing the Age of Animation from Taiwan. University of Hawai‘i Press, 2019. https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/puppets-gods-and-brands-theorizing-the-age-of-animation-from-taiwan/

“UNIMA-USA: Union Internationale de la Marionnette.” UNIMA-USA, https://www.unima-usa.org/.

“Worlds of Puppetry Museum.” Center for Puppetry Arts, https://puppet.org/programs/worlds-of-puppetry-museum/

“Shadows, Strings & Other Things: The Enchanting Theatre of Puppets.” Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, 2019, https://moa.ubc.ca/exhibition/shadows-strings-and-other-things/

“Shadows, Strings & Other Things – Digital Exhibit.” ShadowStringThings.com, https://www.shadowstringthings.com/

“Exhibition Catalogue.” Shadows, Strings & Other Things, https://www.shadowstringthings.com/_files/ugd/3c030d_deba4d754da04d3c90b406224f967549.pdf

“Curatorial Commentary.” Shadows, Strings & Other Things, https://www.shadowstringthings.com/_files/ugd/3c030d_23b38b3f61dd452391da572d802a4ed1.pdf

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank the Center for Puppetry Arts for its dedication towards education within its exhibits and curation. I also want to acknowledge the authors, curators, puppeteers, and communities whose artistic expressions form the foundation of this study.

Leave a comment