On the Shoulders of Giants

Fantastic and Fallacious Archaeology: Part Two

Throughout human history, tales of giants have been a key part of world mythology and creation myth, fascinating the imagination. These colossal figures appear in the mythologies of nearly every culture, with giants representing some of our most formidable foes (like Polyphemus, the blind cyclops in Homer’s Odyssey), as well as our most tragic victims (like the guardian of the Cedar Forest, Humbaba from the Epic of Gilgamesh). Our “heroes” outwit and defeat these towering characters in stories old and new. From the ancient battles of Greek Titans, to the biblical confrontation between David and Goliath, giants have invoked an idea of strength and prowess far beyond our own, as well as posing the primordial mystery of how the world came to be. Ymir’s body forming the world after being killed by Odin and his brothers in the Prose Edda is a perfect example of such a myth. The idea of beings larger than life has been a recurring motif throughout history, shaping the way people envision creation and morality.

These myths did not just fade with the ancient world. In fact, during the nineteenth century, religious fundamentalism had begun to take root widespread among practicing Christians. The stories and legends compiled within the Bible were no longer seen as just allegory or myth, but as literal historical truths of the past. Giant lore found new life in archaeological hoaxes and popular pseudoarcheology, exploiting cultural fascination with the idea that giants once roamed the earth. While hoaxes such as the Cardiff Giant deceived thousands, legitimate archaeology has steadily provided real insights into the validity of humanity’s history. By tracing myths, frauds, and genuine discoveries, we can better understand why people remain captivated by giants and how science can help distinguish fact from fantasy.

Beyond ancient scripture and myth, giants have lived in folklore and oral traditions across the globe. Jack and the Beanstalk is an English fairytale first appearing in 1734 as The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean, although scholars believe it can possibly be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European story The Boy Who Stole Ogre’s Treasure, dating as far back as 4500–2500 BCE. In its original form, the story was less a moral tale and rather a thrilling adventure in which the mischievous Jack outwitted a much larger foe. Over time, adaptations moralized Jack’s theft, casting the giant as a murderer whose death was justified retribution. Giants in folktales often serve as the obstacle and journey for human ingenuity to shine.

In North America, Paul Bunyan became an archetypal tall-tale figure. The lumberjack of folklore stood seven feet tall with strides to match, accompanied by Babe the Blue Ox, whose legendary size reshaped landscapes and created rivers. Paul Bunyan’s popularity in the early twentieth century highlights how larger-than-life figures helped build a sense of national pride and identity, turning the giant into a distinctly American cultural symbol. I remember first learning about Paul Bunyan and Babe in Disney’s American Legends collection back in 2002. The animated short Paul Bunyan (1958) was included in the anthology, and my younger brother and I would watch it over and over again, seeing Paul and Babe wrestle and form the landscape of the American Midwest, introducing the giant lumberjack to new generations like my brother and me.

While myths served symbolic and cultural purposes, they were often intertwined with real-world phenomena. In antiquity, the unearthing of large fossilized bones like mastodons, mammoths, or even whales was easily misinterpreted as proof of giant humans. Lacking knowledge of comparative anatomy, people often viewed these remains as validation to their beliefs. Misguided paleontological discoveries fueled legends and reinforced belief in what the Bible and oral tradition already proclaimed. By the nineteenth century, the fascination with giants had become the ground for hoaxes fueled by mystery, profit, and blind belief.

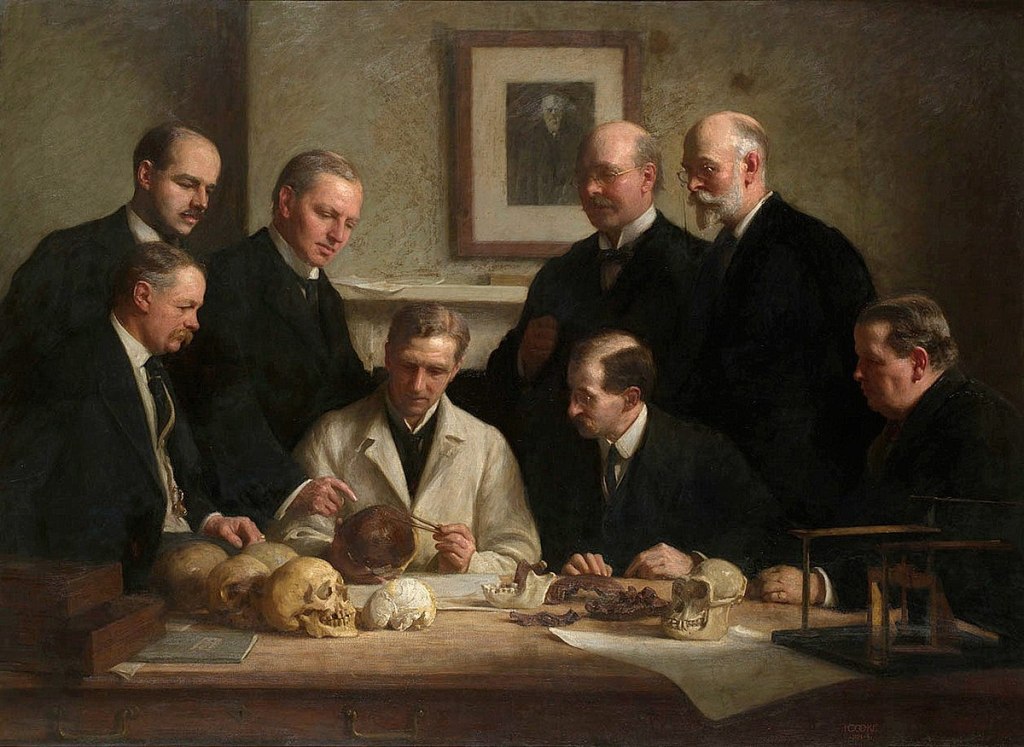

The most famous of these hoaxes was the Cardiff Giant, discovered on October 16th, 1869 on a farm in the upstate town of Cardiff, New York. Workers digging a well behind the barn of farmer Stub Newell encountered what appeared to be the petrified remains of a ten-foot-tall man. Almost immediately, the discovery became a sensation. Newell charged visitors fifty cents to view the giant, and within the 3 week period he had the giant on display, thousands had flocked to see it, with profits equivalent to at least $674,000 in modern currency. Newspapers dubbed it the “Goliath of New York,” and fundamentalists saw it as physical proof of the Bible’s accounts of ancient giants roaming the earth before the Biblical flood. Professional geologists and paleontologists were skeptical from the start, noting tool marks on the surface and the softness of the stone, agreeing that the statue was ultimately a carving. By December of that year, George Hull, a cigar manufacturer and cousin of Newell, confessed to the fraud. Hull had commissioned a massive gypsum statue, artificially aged its surface, and secretly buried it on Newell’s farm a year before its “discovery.” Hull sought to expose the gullibility of people while making a profit after an argument with a minister regarding the literal truth of the Bible. The hoax did not stop there however, as showman P. T. Barnum commissioned a replica of the giant that was carved in 1972 when denied the chance to exhibit the original. The fake continued to make money, showing just how deep the desire to believe could override scientific skepticism.

Why do people believe in giants, even in the face of contradictory evidence? The cultural psychology of religion played a major role in the acceptance of the Cardiff Giant; for many nineteenth-century Americans, the discovery seemed to confirm their biblical truth. More broadly speaking, the idea of giants appeal to a love of mystery and the unknown. The notion that colossal beings once roamed the earth was exciting in a way that every day archaeology may not be. Money is, and was, a big factor as well: a good hoax generates tourism and profit, as seen in both Newell’s farm in New York, and P. T. Barnum’s replica of the fake giant. Giants also serve symbolic purposes, offering communities a source of identity in these figures, for example how the folklore of Paul Bunyan created a giant lumberjack representing American industry and expansion.

The persistence of giant hoaxes owes a lot of its fire to conspiracy narratives. Anthropologist Andy White discusses in his article Antient Giants the oddly frequent historical reports of “giant” skeletons being excavated in the eastern Woodlands of North America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and how this renaissance is tied into religious fundamentalism, along with the idea that correlations are not explanations in and of themselves. The role of a correlation is to prompt further inquiry, not to provide enough evidence on its own. It’s a signal that something interesting is happening, and it’s our job to figure out why, and White does just that. I really appreciated the extensive research he did in providing so many resources regarding this topic of ancient giants in the eastern Woodlands, it was honestly very inspiring as I love research as well. His analysis demonstrates how volume of reporting can create an illusion of truth, even when the underlying claims lack scientific verification. Reading his work highlighted the necessity for critical evaluation; what seems like overwhelming proof may just be the product of repeated misinformation.

In Jason Colavito’s article How David Childress Created the Myth of a Smithsonian Archaeological Conspiracy, Colavito highlights how pseudohistorian and author David Hatcher Childress has popularized the conspiracy that the Smithsonian Institution orchestrated a cover-up to suppress evidence of giant skeletons found in Native American burial mounds. Colavito’s investigation into the origins of the so-called Smithsonian conspiracy further illustrates how pseudoarcheology can take root, demonstrating how these claims were built not on factual evidence, but on misrepresentation and sensationalism. I really felt that this article was important because it reveals the cultural and political conditions that make theories like this tempting to people distrustful of institutions, appealing to people’s distrust of the government and overall paranoia. Although Childress’s claims and “evidence” came from the early 90s, I feel like today more than ever we are seeing a rise in these same ideals, and this article was a powerful reminder that we must seek out factual evidence and verifiable data.

Despite all of the hoaxes and fraudulent claims surrounding this topic, genuine archaeology demonstrates that the truth can be equally fascinating without resorting to myth. In 2016, archaeologists excavating a late Neolithic site at Jiaojia in the Northeastern Shandong Province of China, uncovered a burial ground where several men were unusually tall for their time, standing over 5’9” and taller. Compared to the average Neolithic European male height of 5’5”, these individuals would have been giants for their time, with one individual measuring in at 6’2”, or 1.9 meters tall. Their stature was likely due to better nutrition and social status, suggested by the placement of pottery and jade artifacts in their rather large tombs.

These findings highlight how legitimate science can explain variations in human size through diet, environment, and genetics, rather than through some lost race of pre-flood titans. Real discoveries also demonstrate how context matters. By examining the burial practices, settlement patterns, and associated artifacts at a given site, archaeologists can build an understanding of what ancient life could have been like that hoaxes and pseudoarcheology ignore. This also highlights how important public education is when combating pseudoscience. When people understand how archaeology works, they are less likely to be swayed by bias claims of lost giants or hidden conspiracies. Moreover, genuine discoveries like the Jiaojia burials reveal that reality often provides wonders equal to myth. Humans have always varied in size, strength, and stature, and these differences can tell us much about diet, environment, and social organization in the past.

In the end, giants continue to hold sway over our imagination because they embody our ability to dream big. Myths of giants connect us to ancient fears and aspirations of the cultures that created them, while hoaxes remind us how easy people’s beliefs can be exploited. But archaeology shows us that not everything has to be centered around fraudulent claims. The Jiaojia “giants” of China were not ten feet tall or supernatural beings, but men who stood taller than those around them. They remind us that the human story is filled with variety and wonder even without embellishment, and by appreciating real discoveries while remaining skeptical of supernatural claims, we can honor both the creativity of cultural storytelling and the validity of scientific inquiry. Giants, whether mythical or fraudulent, reveal more about our human desire to believe than about the past itself. But archaeology, when carefully practiced, ensures that truth, however ordinary it may seem, remains our surest guide to understanding where we come from. Our knowledge of the known world is built and shaped by the real discoveries and work of thinkers before us, not mythical titans, to advance our understanding of the world. To quote Isaac Newton, “if I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants”.

Works Cited/References/Acknowledgements

American Literature. Jack and the Beanstalk. AmericanLiterature.com, https://www.americanliterature.com/childrens-stories/jack-and-the-beanstalk.

Colavito, Jason. “How David Childress Created the Myth of a Smithsonian Archaeological Conspiracy.” Jason Colavito Blog, 2014, https://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/how-david-childress-created-the-myth-of-a-smithsonian-archaeological-conspiracy.

Encyclopedia Britannica. “Giant.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/giant-mythology.

Feder, Kenneth L. “Anatomy of an Archaeological Hoax.” Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. 8th ed., Oxford University Press, 2013

Mental Floss. “10 Mythical Giants Around the World.” Mental Floss, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/84109/10-mythical-giants-around-world.

Smithsonian Magazine. “Graveyard of Giants Found in China.” Smithsonian Magazine, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/graveyard-giants-found-china-180963976/.

White, Andy. “Ancient Giants.” Andy White Anthropology, https://www.andywhiteanthropology.com/ancient-giants.html.

Leave a comment