“Lost Tribes” of the New World

Fantastic and Fallacious Archaeology: Part Four

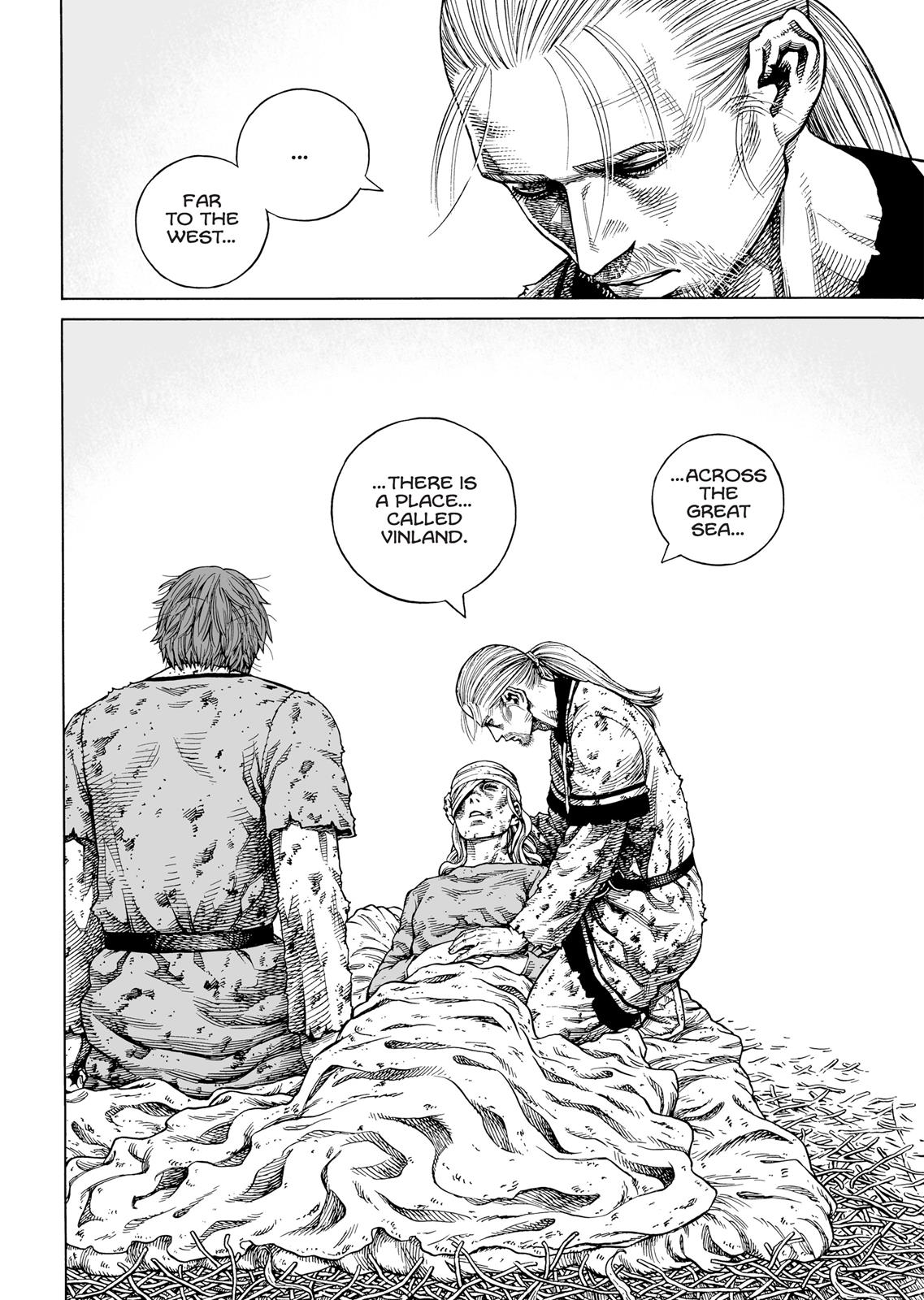

“Far to the west, across the sea, there is a place called Vinland. It is warm and fertile, far from slavery and the fires of war. No one can reach you there.”

— Thorfinn Thorsson, Vinland Saga

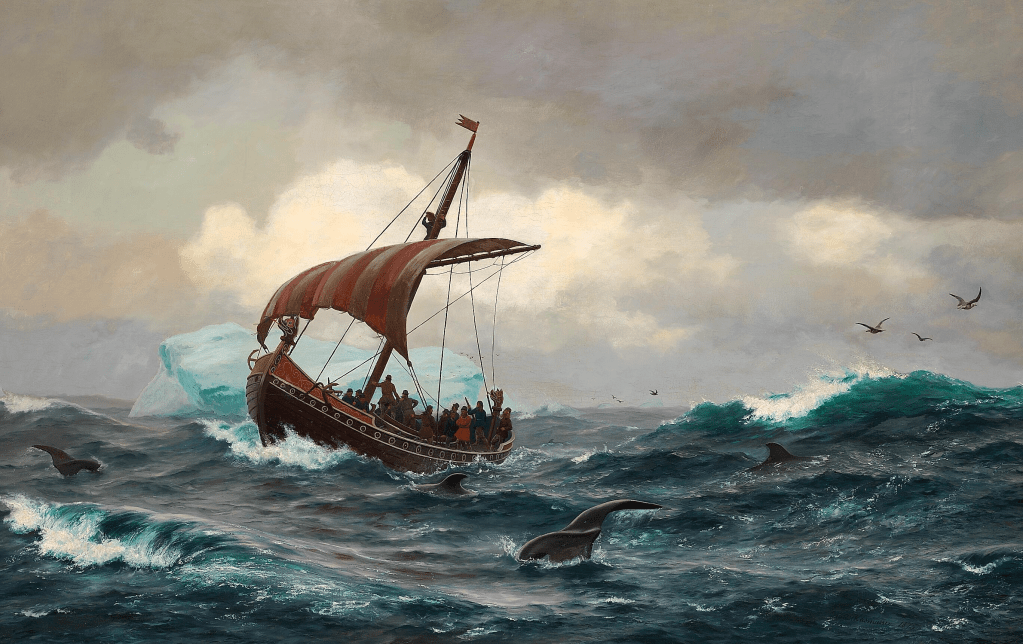

I have always been drawn to the restless curiosity of explorers in history, especially those whose stories and journals have helped us look beyond the map’s edge in search of a deeper understanding of one another. Craving to see the world, I continue to find myself envious of the journeys of these adventurers, hungry for the knowledge and cultures they stumbled upon. Leif Erikson was definitely a big one for me (and my younger brother, Spence); my middle school used “Leif Erikson Day” as an educational opportunity to learn about the Norse explorer who travelled to modern day Newfoundland almost 500 years before Christopher Columbus had set foot into continental America. When I was 12, I did a report on The Vinland Sagas, two Icelandic texts recounting the voyages to Vinland from Greenland, comprised of The Saga of Erik the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders, and are said to have taken place between 970 and 1030 in North America. What a joy it was to discover that there was a manga inspired by the very stories my brother and I loved learning about back then.

In Makoto Yukimura’s manga Vinland Saga, we follow our protagonist Thorfinn (based on the real explorer Thorfinn Karlsefni) and his journey west to settle in “Vinland”. Thorfinn’s personal transformation and longing for discovery mirrors our own urge to search for new beginnings within ourselves and in the world around us. Yukimura uses archaeological contexts (like Viking settlements, weapon types, clothing, and social structures) as a way to retell the original Vinland Sagas through the eyes of Thorfinn, building intricate narratives on top of them. Within the story we see many central themes like violence and cultural contact, as well as colonization and migration. While some creative liberties are taken, Vinland Saga aligns closely with archaeological records from sites in Iceland, Greenland, Norway, and Newfoundland. This interplay reflects how anthropologists and archaeologists interpret past cultures through both material remains and ethnographic analogy. Archaeology, like Thorfinn’s voyage westward, is a continual pursuit of understanding and sailing through uncertainty, with the hopes of uncovering the truths buried beneath the stories we tell about the past.

Panels from Makoto Yukimura’s manga Vinland Saga

Throughout history, people have sought to trace their roots to something bigger: the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, Romans adrift in the Arizona desert, or Welsh princes founding kingdoms in the New World, our yearning to connect ourselves to ancient greatness often clouds the evidence that lies quite literally beneath our feet. Let’s dive into how the myths of “lost tribes” emerged, how genuine archaeological science has re-anchored the conversation, and how real sites show us the incredible ingenuity of our past.

When Europeans like Amerigo Vespucci and Christopher Columbus first encountered the native peoples of the Americas, they came face-to-face with their misconceptions of the New World. When discussing claims about “lost tribes,” I think it’s important to keep in mind that early Europeans frequently tried to situate the Indigenous peoples they encountered within a biblical context. Kenneth Feder writes in his book Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology how Europe was less interested in who Indigenous peoples were and more so how they fit within a biblical worldview. Sixteenth-century scholars scrambled to tie in scripture with these new discoveries, suggesting that Native Americans must be the descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, the exiled peoples said to have disappeared from historical records after the Assyrian conquest in 722 BCE. This argument felt plausible in a time when superficial cultural similarities were treated as proof of direct descent. Observers noted that some Indigenous groups practiced circumcision or shared myths about floods and journeys; therefore, they must be Israelites. Feder calls this early approach “trait-list archaeology”: the practice of linking groups through cherry-picked similarities and superficial likenesses without context or chronology.

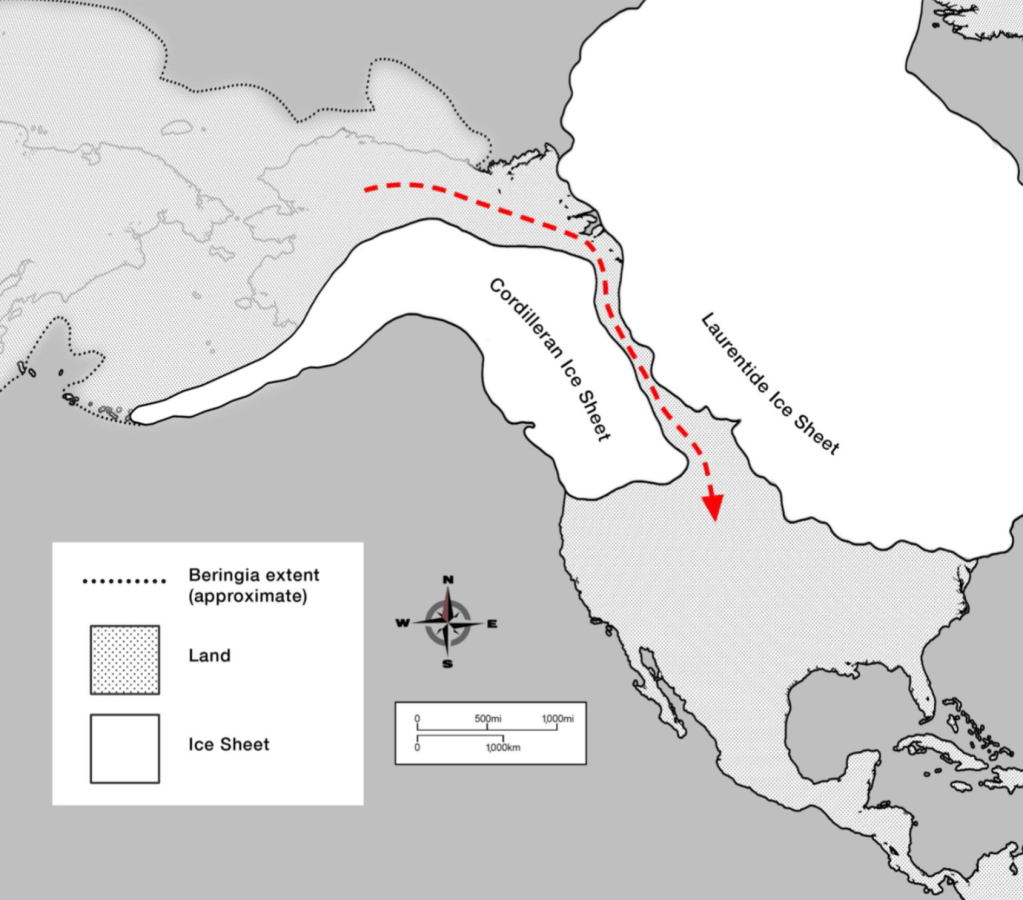

But not everyone accepted this lack of methodology. In 1590, Friar José de Acosta, a Jesuit missionary in Peru, published one of the most important works examining the origins of Native people in the New World: The Natural and Moral History of the Indies. After seventeen years in Peru, Acosta observed that if animals had crossed from the Old World to the New, then surely people could too. His deduction implied a land connection: that Asia and America were once connected, predating the idea of the Bering Land Bridge by nearly two centuries. During the Pleistocene epoch, sea levels dropped nearly 400 feet, exposing the Bering Land Bridge, a thousand-mile corridor linking Siberia and North America. Acosta’s reasoning was remarkable because it relied on observation rather than revelation, seeking a natural explanation without blindly relying only on his faith.

While some thinkers like Acosta prefigured a scientific understanding of human migration, many explorers preferred to imagine more… creative routes. Feder recounts how the Spanish colonist and writer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in his General and Natural History of the Indies (1535) imagined the first Americans as lost merchants and refugees from ancient Carthage, or the followers of King Héspero (Hesperus), a mythic Spanish ruler who fled Europe in 1658 BCE (according to Feder).

In the article Spain Used Ancient Myth And Legend In An Attempt To Bolster Its Claims On The New World by C. Keith Hansley from The Historian’s Hut, he mentions how “one of the more curious ways that Spain tried to bolster its ownership of the New World involved harkening back to ancient legend and myth. In particular, patriotic Spanish scholars mused over the tales of Hesperus—the personified evening-star god, who came to be associated with the Iberian Peninsula and the Canary Islands.” Theologians and patriots alike found comfort in claiming Indigenous ancestry for Mediterranean peoples; to the Spanish, who could therefore assert that Columbus had only rediscovered and reclaimed what was already theirs.

“The islands known as the Hesperides mentioned by Sebosus and Solinus, Pliny and Isidore must undoubtedly be the [West] Indies and must have belonged to the Kingdom of Spain ever since Hesperus’s time, who, according to Beroso, reigned 1,650 years before the birth of Our Lord. Therefore, if we add the 1,535 years since Our Saviour came into the world, the kings of Spain have been lords of the Hesperides for 3,193 years in all. So by the most ancient rights on this account and for other reasons that will be stated during the description of Christopher Columbus’s voyages, God has restored this realm to the kings of Spain after many centuries. It appears therefore that divine justice restored to the fortunate and Catholic Kings Ferdinand and Isabel, conquerors of Granada and Naples, what had always been theirs and belongs to their heirs in perpetuity”

— Oviedo, General and Natural History of the Indies

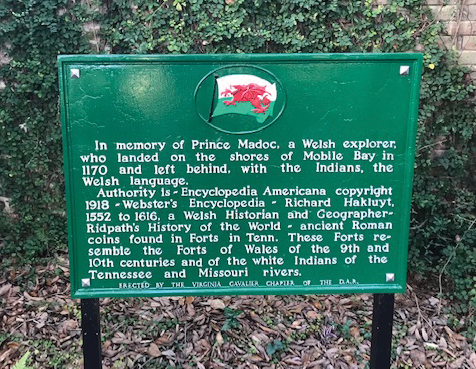

Another famous example of national legend taking root here in the Americas comes from Prince Madoc of Wales, a legendary sailor who supposedly set out in 1170 and discovered America centuries before Columbus. In the nineteenth century amateur historians cited supposed “Welsh forts” in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and Kentucky as evidence of Madoc’s colony and Welsh presence. When mainstream archaeologists demonstrated that the structures were Indigenous, believers simply “relocated” the legend. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) erected a historical marker on the shore of Alabama’s Mobile Bay in 1953 commemorating Madoc’s “landing,” which was blown down by Hurricane Frederic in 1979. Stories like this continue to shine light on how archaeology was often used in service of national myth-making and legend.

Pseudoarcheology often thrives where evidence is thin and imagination is thick, relying on belief rather than knowledge. It becomes a problem of epistemology as much as a scientific one: a question of how we know what we claim to know about the past, and how fragile our ways of “knowing” can be without scientific method. Archaeology, by contrast, roots its knowledge in context and verifiable evidence, with patient reconstruction of truth rather than the invention of it.

Let me introduce you to the case of the Oreo cookie conspiracy. Internet theorists once claimed that the cookie’s design secretly encoded symbols of the Knights Templar and Freemasons, with its cross motifs mistaken for medieval insignia. The truth, of course, has a lot less to do with secret societies and more with general design and aesthetics. The first chairman of the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco), Adolphus Green, happened to find the design while looking through his collection of rare books. It was a 15th century pressmark used by the society of Printers in Venice, which derived from an even earlier symbol of “spiritual triumph over the worldly” in the early Christian era. I think it’s hilarious but fascinating that even snacks can become the objects of pseudo-history.

Of course, there are much more serious examples: In 1976, Ivan Van Sertima’s book They Came Before Columbus proposed that West African sailors reached Mesoamerica long before Europeans, basing the claim on Columbus’s mention of “black Indians”, and the “Negroid” features of the stone Olmec colossal heads. Despite these (frankly racist) claims, archaeologists note that the basalt head sculptures resemble local populations, not Africans. Van Sertima ignores the fact that these statues have broad flat faces and epicanthic folds typical of many Asians and Native Americans, a lack of prognathic (jutting) features more common to Africans, and the cultural contexts that fit within the Indigenous artistic traditions of the region. He completely overlooks the lack of archaeological evidence that would point to African exploration prior to Europeans bringing enslaved peoples to the New World. No African artifacts, ship remains, or genetic traces accompany these claims.

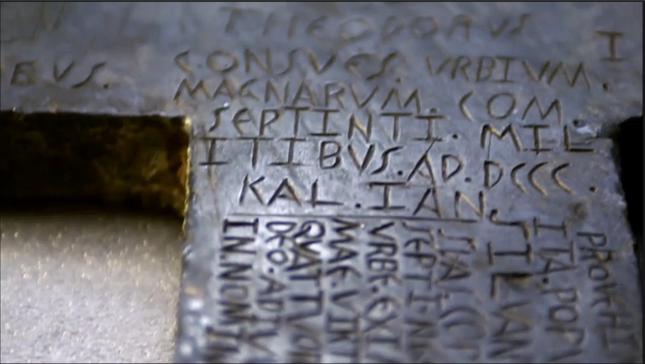

Similarly, in 1924 the Tucson Artifacts, a collection of 31 various lead objects (inscribed crosses, crescents, batons, swords, and spears) were allegedly found in some old lime kilns near Arizona’s Picture Rocks. Enthusiasts declared the discovery as evidence of a Roman Judeo-Christian colony. Archaeologists and scholars were skeptical, and microscopic analysis later revealed modern tool marks, as well as a local news article identifying a Mexican sculptor Timoteo Odohui who lived near the site in the 1880s as the possible creator. The desire to elevate American soil into an extension of the Old World outweighed critical methodology, with Western audiences jumping to imagine Israelites or Romans in America and the idea that “civilization” reached these continents early.

Assorted collection of the Tucson Artifacts.

Now, lets get into the real archaeology:

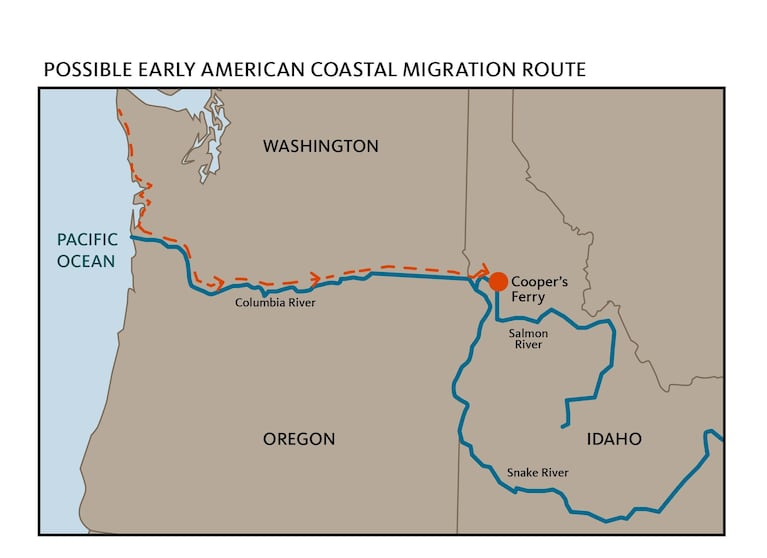

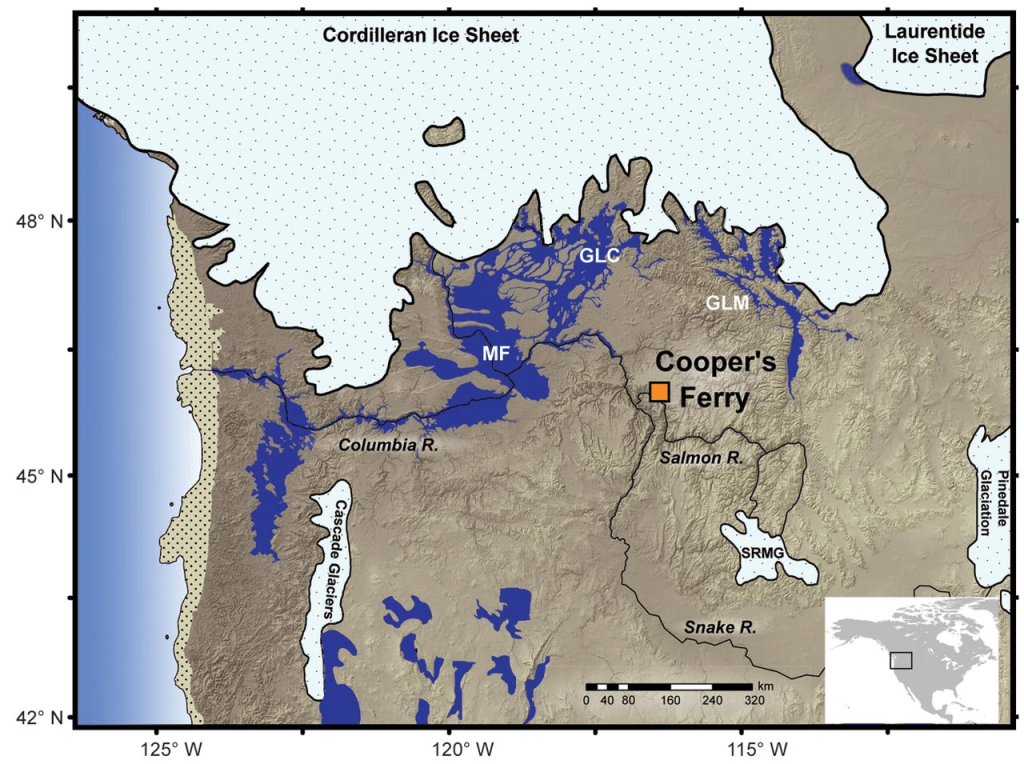

In Douglas Main’s article First People in the Americas Came by Sea, Ancient Tools Unearthed by Idaho River Suggest, published on Science.org, researchers excavating the Cooper’s Ferry site along Idaho’s Salmon River found stone tools, hearths, and butchered animal bones dating to roughly 16,000 years ago. Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University and project lead for the Cooper’s Ferry site, notes that the site’s location supports a “coastal migration” hypothesis. The site is situated more than 500 kilometers inland, but connected by the Salmon, Snake, and Columbia rivers to the Pacific. These early peoples likely followed waterways southward along the Pacific coast, long before the inland ice-free corridor opened through Canada roughly 14,800 years ago.

All of this challenged the long-held “Clovis-first” model, which held that the Clovis people, big game hunters who made characteristic stone tools dated to about 13,000 years ago, were the first to reach the Americas, presumably through the ice-free corridor. In Main’s Science article, he writes how David Meltzer, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, expresses that the stone tools and dating at Cooper’s Ferry are generally acknowledged as pre-Clovis, going as far as saying “It’s pre-Clovis. I’m convinced.”

The lithic technology resembles spear points found in Hokkaido, Japan, hinting at deep cultural links between Ice Age Northeast Asia and North America, and the hypothesis that the first Americans didn’t arrive by land, but by boat. I personally found this deeply fascinating as I originally studied Japanese in college in 2017 and focused a lot of my research on Japan’s Indigenous Ainu and the preservation of their culture in the modern day.

Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) writer Erin Ross expands this research further in her article North America’s Oldest Human Artifacts Found In Idaho, archaeologists discovered nearly 200 items at Cooper’s Ferry dating 16,500-15,000 years ago, at a time when the north-central corridor was still blocked by ice, and that among the artifacts recovered, they continuously found stemmed points that were extremely similar to a type found in Hokkaido, also dated to around 16,000 years old. For a deeper look at the excavation’s methods and chronology, Davis’s full research publication provides a more in depth analysis.

Meanwhile, in Jennifer Raff’s Sapien’s article A Genetic Chronicle of the First Peoples in the Americas, emphasizes how genomic studies have traced Indigenous Americans back to a founding population in Northeast Asia that lived in Beringia for millennia before expanding across the hemisphere. Raff also highlights how ancient DNA refutes earlier “Paleoamerican” models based purely on cranial morphology claims, such as the idea that Kennewick Man represented a lost European lineage. Instead, he shares deep genetic continuity with modern Native Americans.

The complementary use of lithic typology, radiocarbon dating, and ancient genome studies shows how we move from “lost tribes” rhetoric to more grounded models of migration and settlement of ancient and Indigenous peoples. To call Indigenous Americans “lost” or “immigrants” overlooks the vast endurance of ancient peoples who, over tens of thousands of years, adapted, diversified, and flourished within these landscapes.

When we talk about “lost tribes,” often what is missing is the respect for the living descendants of those ancient peoples. Indigenous voices and traditions are not silent, they hold memories of migration and traditions of the past. Archaeology that treats Indigenous peoples as passive or “lost” fails to respect the living cultural landscape, and myth-hungry narratives of lost tribes obscure that ongoing story. As Choctaw archaeologist Dorothy Lippert wrote, “for many of our ancestors, skeletal analysis is one of the only ways that they are able to tell us their stories.” And, although “it is difficult to speak with a voice made of bone,” it is the job of archaeologists to listen and use science to learn what we can about their lives.

Real archaeology also re-examines the encounters that truly happened. The Hernando de Soto expedition left one of the earliest European footprints on what is now Florida. This project from the Florida Division of Historical Resources, Hernando de Soto 1539–1540 Winter Encampment at Anhaica Apalachee, highlights the excavations at Anhaica Apalachee and how material evidence from the winter encampment of Hernando de Soto provides a link between de Soto’s textual accounts and Indigenous built landscapes. Archaeologists unearthed evidence of Spanish armor fragments, crossbow bolts, and glass trade beads, matching accounts from de Soto’s chroniclers describing the Apalachee province of Anhaica, near modern Tallahassee. Here, archaeology truly becomes a recovery effort. The material record shows a highly organized Apalachee society that maintained its agricultural and political systems even under violent intrusion. Rather than being a “lost tribe,” they were a documented and enduring community, one whose story survived in the soil chemistry and artifacts recovered.

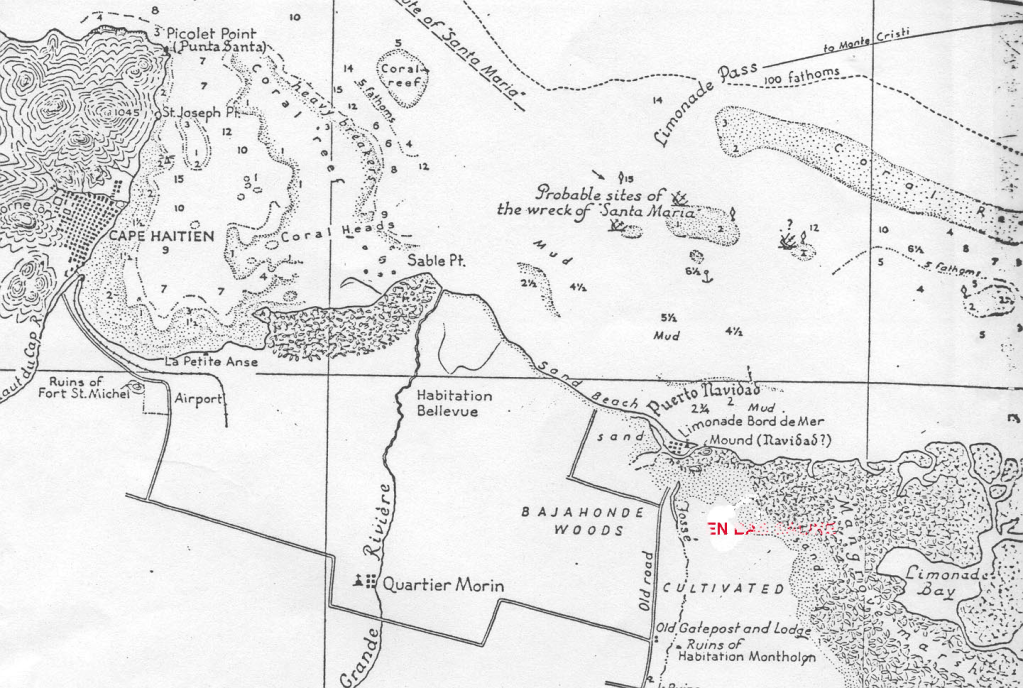

Similarly, Kathleen Deagan’s report En Bas Saline at the Florida Museum of Natural History documents excavations of a Taíno town on Haiti’s north coast, occupied between 1200 CE and 1530 CE. The site corresponds to cacique Guacanagarí’s capital, the same place where Columbus built his ill-fated fort of La Navidad after the Santa María wrecked. Excavations show that while the Spanish outpost lasted only months, Taíno occupation persisted for centuries. Pottery, shell ornaments, and imported beads testify to trade and adaptation, a narrative often erased by colonial documents. As Deagan’s team concludes, “there is no archaeological indication that Europeans lived at En Bas Saline after La Navidad was abandoned.”

Among all of the “lost tribe” legends, perhaps one of the most widely recognized is the Vikings sailing to North America. For centuries scholars debated whether Vinland was mythic, but that debate ended when Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad and his wife, archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, discovered L’Anse aux Meadows in 1960. Excavations of the site brought further discovery: turf houses, an iron-smithing site, a boat shed near the modern hamlet of L’Anse aux Meadows, iron nails, and artifacts dated around 1000 CE, unmistakably Norse in form. UNESCO listed it as a World Heritage Site in 1975, and is the first and only known site established by Vikings in North America, not to mention being the earliest evidence of European settlement in the New World.

As mentioned at the start, The Vinland Sagas describe the voyages led by Leif Erikson, Bjarni Herjólfsson, and Thorfinn Karlsefni to a land they called Vinland. According to those texts, they built houses of sod, met Indigenous peoples (who they referred to as Skraelings), traded, fought, and ultimately retreated after a few seasons. This site’s significance merges storytelling and science, material culture, and Indigenous history. It marks the moment when the Old World and the New first met across the North Atlantic centuries before Columbus, showcasing that meaningful contact did happen, despite how fleeting it may have been.

If we map all these cases: from Idaho to Haiti, Florida to Newfoundland, and “Carthage to Cathay”, a pattern emerges opposite of what mythmakers claimed. Instead of foreign tribes populating an “empty” continent, archaeology reveals continuous Indigenous presence with episodic contacts from abroad, with their stories often buried under colonial and nationalistic projection. The Knights Templar etched into Oreo cookies, or Welsh princes turned classroom legend show how modern societies still mythologize the past to claim some kind of lineage to the New World. The notion of “lost tribes” often tells us more about modern desires than ancient realities.

In 1021 CE, Norse explorers cut down fir trees on a Newfoundland hillside. The wood was abandoned along with L’Anse aux Meadows, untouched for a millennium. A thousand years later, scientists traced the iron tool-marks and dated them to that exact year: an astonishing testimony to the exploration within The Vinland Sagas. In a 2021 study, scientists were able to conduct tree ring analysis by using a new method that examined ring growth from radioactive carbon-14 caused by a solar storm in 993 CE that showered the Earth with high energy particles. The spike in the number of tree rings allowed the scientists to pinpoint the exact year the Vikings cut the trees.

I don’t know why this was so incredible to me, but the thought of someone holding that piece of wood 1,000 years ago, and for us to hold it today, knowing it is part of something so profound really gives me chills. I think it truly encapsulates the beauty of archaeology. The Viking site at L’Anse aux Meadows proves that the boundary between legend and evidence isn’t always a wall; sometimes, it’s a bridge. But as every good explorer (or archaeologist) learns, a bridge must rest on solid ground.

Works Cited/References/Acknowledgements

Main, Douglas. “First People in the Americas Came by Sea, Ancient Tools Unearthed by Idaho River Suggest.” Science, 2019, https://www.science.org/content/article/first-people-americas-came-sea-ancient-tools-unearthed-idaho-river-suggest

Ross, Erin. “North America’s Oldest Human Artifacts Found in Idaho.” OPB, 29 Aug. 2019, https://www.opb.org/news/article/oregon-state-university-oldest-human-artifacts-idaho-north-america/

Davis, Loren. “Evidence for Coastal Migration and Early Occupation of North America: Stone Tools from Cooper’s Ferry.” Science, vol. 373, no. 6562, 2021, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aax9830

Raff, Jennifer. “A Genetic Chronicle of the First Peoples in the Americas.” Sapiens, 8 Feb. 2022, https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/ancient-dna-native-americans/

“Archaeological Investigations at Anhaica Apalachee (1539–1540).” Florida Division of Historical Resources, https://dos.fl.gov/historical/archaeology/projects/hernando-de-soto-1539-1540-winter-encampment-at-anhaica-apalachee/

“En Bas Saline, Haiti.” Florida Museum of Natural History https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/histarch/research/haiti/en-bas-saline/

“L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/4/

Maher, John. “Madoc’s Marker: The Persistence of an Alabama Legend.” Mobile Bay Magazine, 15 June 2019, https://mobilebaymag.com/madocs-mark-the-persistence-of-an-alabama-legend/

Hansley, C. Keith. “Spain Used Ancient Myth And Legend In An Attempt To Bolster Its Claims On The New World.” The Historian’s Hut, 28 Feb. 2021, https://thehistorianshut.com/2021/02/28/spain-used-ancient-myth-and-legend-in-an-attempt-to-bolster-its-claims-on-the-new-world/

Nature Editors. “Tree-Ring Dating Confirms Viking Age in Newfoundland.” Nature, vol. 600, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03972-8

“Top of the World: L’Anse aux Meadows – Viking Settlement.” YouTube, uploaded by HistoryTravel, 18 May 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KA2LXDu1dlw

Feagans, Carl. “The Tucson Artifacts Hoax.” A Hot Cup of Joe, 9 Jan. 2025, ahotcupofjoe.net/2025/01/the-tucson-artifacts-hoax/.

Feder, Kenneth L. “Who Discovered America?”, “Who’s Next? After the Indians, Before Columbus” and “The Myth of the Moundbuilders,” Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. 8th ed., Oxford University Press, 2013

Leave a comment