Fabulous Creatures and the Missing Link

Fantastic and Fallacious Archaeology: Part Three

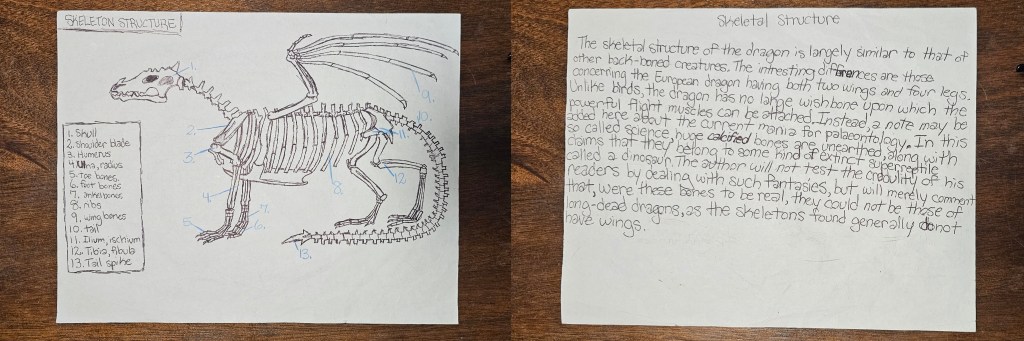

It was 2005, Christmas morning, and I was opening up all of my presents with my family. I always asked for books (or videogames) for gift ideas to my family, and I was over the moon to see I had gotten the two books I had asked for on my wishlist: Dragonology and Wizardology by Dugald Steer. I used to play “wizard school” and re-draw the diagrams and skeleton studies from the book, and would go looking for dragons in the woods by my house in Tennessee. These “Ology” books were written in an encyclopedia/academic style and explored a range of topics around the unknown, from myth and legends to creatures and monsters. In our lecture topic from this week, I was reminded of these books and my curiosity about these mysterious and fantastical “unknowns”. That fascination with the uncanny, from fabulous creatures in early modern compendia to staged “missing links” in paleoanthropology, the tension between myth and science has shaped our understanding of humanity.

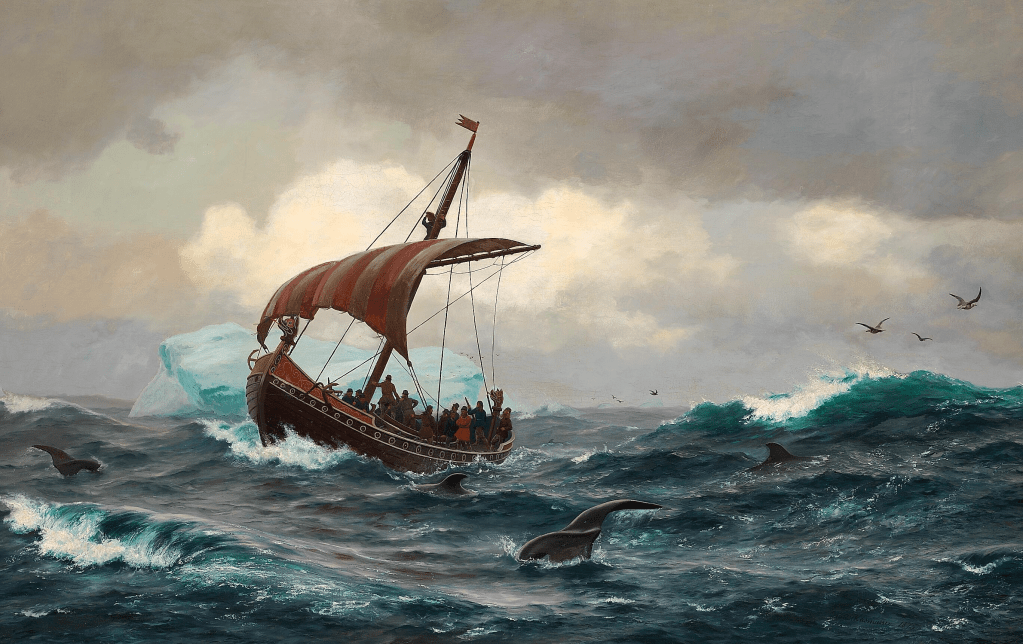

In the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s article “Monsters, the Scientific Revolution, and Physica Curiosa,” the author explores how early modern Europe’s evolving scientific worldview intersected with longstanding myths about monsters and strange creatures. The piece highlights Physica Curiosa, a compendium from 1662 by Gaspar Schott, which gathers accounts, illustrations, and natural history lore about mythic or monstrous beings (such as Satyrs, chimera-like winged humanoids, and other “monsters” ) and reveals how these stories skirt the fine line between superstition and empirical inquiry. Schott’s Physica Curiosa and Theodor de Bry’s engravings mingled distorted accounts of “wild men,” sea monsters, and centaurs with real ethnographic encounters. During the Age of Exploration European explorers presented the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania as monstrous and fantastical, with these depictions reflecting Europe’s anxieties about the unknown world. These accounts, although fantastical, served as a proto-anthropology: they attempted to classify the unfamiliar and the extraordinary, even if the results were more fiction than science.

Even as the Scientific Revolution in 16th/17th century Europe introduced more rigorous observation and skepticism, this was still a time where empirical science hadn’t fully separated what people wanted to believe from what could be reliably observed. Some monster tales were based on distorted reports of real creatures or sailors’ impressions, others came from imaginative or symbolic traditions. But people didn’t just believe in monsters because of superstition, they believed them because knowledge was scarce, classification systems were still being developed, and exploration was expanding what people thought possible. It challenges the simplistic narrative that myth equates ignorance and rather myth, speculation, and early “errors” were part of the process by which science got better, with people figuring out how to put science in practice by observation and testing the world around them.

P. T. Barnum’s Feejee mermaid became one of the most notorious examples of a fabricated creature. The specimen was constructed from the torso of a juvenile monkey sewn onto the body of a fish, and presented as the mummified body of a mermaid. In a 2016 Live Science article “The Feejee Mermaid: Early Barnum Hoax,” author Jessie Szalay examines the infamous 19th-century hoax and how Barnum was able to promote the specimen as a real mermaid. Barnum generated buzz before the public display by having his associate publish fake letters to newspapers claiming to have encountered a Dr. Griffin (really a man named Levi Lyman who had worked with Barnum on a previous hoax in 1835) who had seen incredible “specimens” including the mermaid. Adrienne Saint-Pierre, curator of the Barnum Museum in Bridgeport, Connecticut, said “Between the two of them they engineered quite a story preceding the public presentation of the Fejee Mermaid … with made-up letters to the papers from people in distant states who claimed to have met a Dr. Griffin from London and had seen his amazing creatures, including the mermaid.”

Although naturalists were eventually brought in and declared the mermaid a fraud, many were less authoritative or less familiar to the public, so their affirmations helped sustain the illusion, which continued to drive the mystery of the Feejee mermaid for guests willing to pay and see the creature. Szalay does a great job highlighting how Barnum’s hoax relied not only on the mermaid itself, but also the carefully orchestrated performances, press, and invented expert authority to create scientific credibility and build up public curiosity surrounding the mermaid.

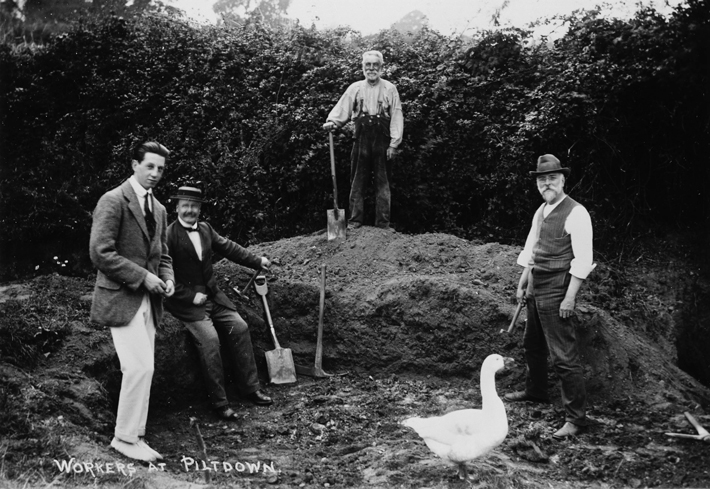

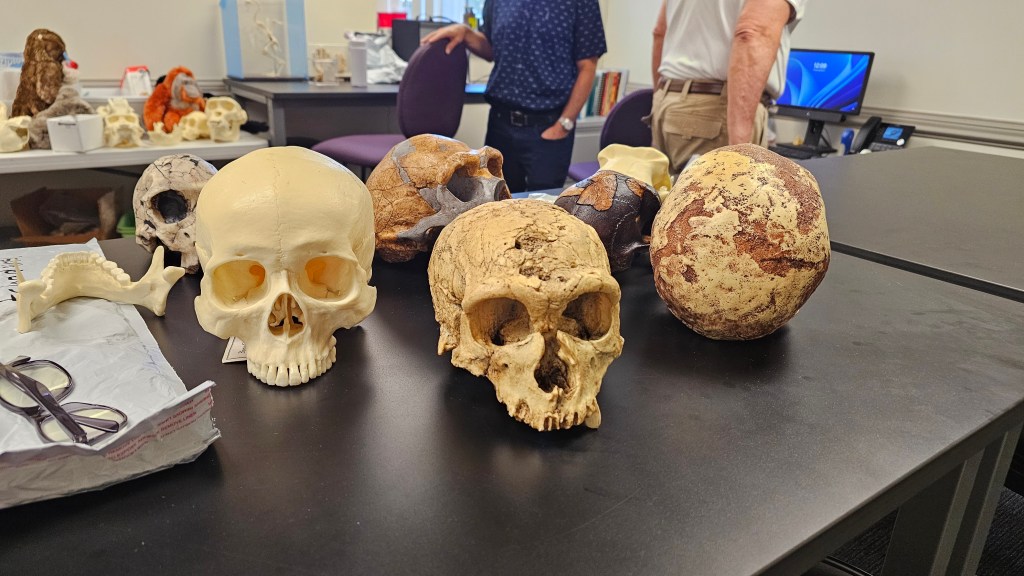

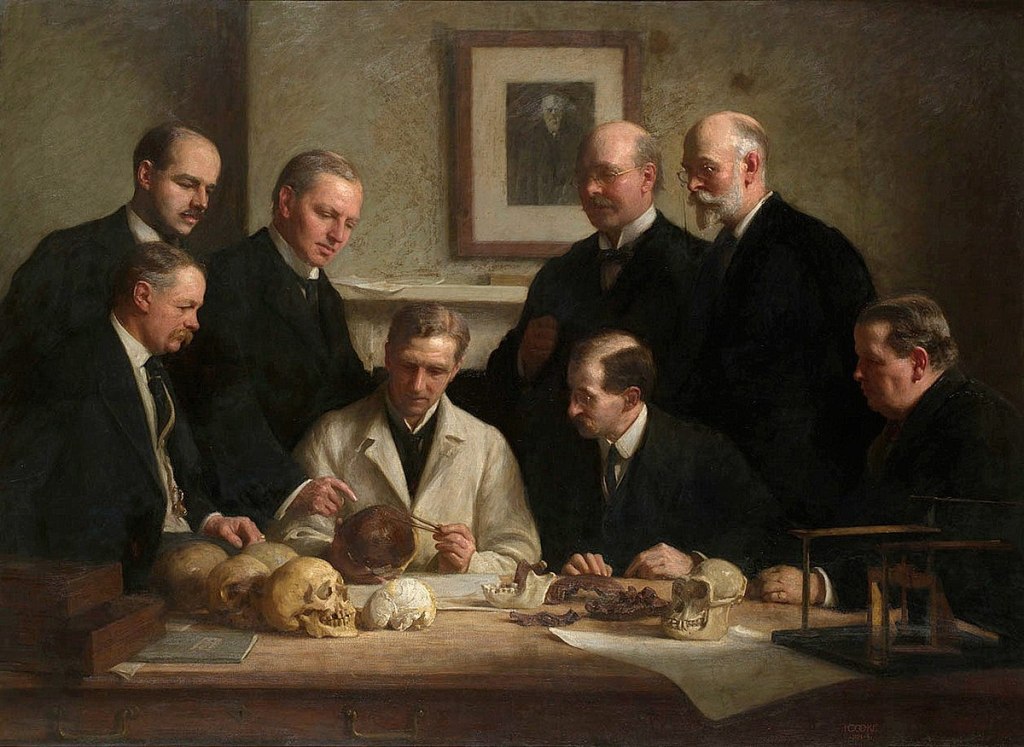

By the 19th century, following Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871), the quest for the “missing link” became a cultural fixation. Darwin’s ideas had shifted science, with many asking: where is the human “missing link”? National pride played an enormous role in this search, with Germany claiming Neanderthals, the French to Cro-Magnons, and “Java Man” for the Dutch, with the Netherlands discovering fossilized remains of a primitive human ancestor in the former Dutch colony of Java. Britain lacked its own fossil evidence of antiquity, and so came Piltdown Man (1912): part skull, part jaw, supposedly dating back roughly 500,000 years ago. Charles Dawson, an amateur scientist, and Arthur Smith Woodward of the British Museum announced in 1912 the discovery of “Piltdown Man” in Sussex, a skull that appeared modern paired with an apelike jaw. The fossil seemed to confirm the “brain-first” theory of evolution, satisfying both British national pride and scientific expectation, allowing Britain to say “we are in the story of humankind’s past.” It looked like a perfect fit for what people wanted to see: a big-brained ancestor, teaching that the brain preceded many “primitive” features.

But decades later, with new dating technology arriving in 1949, geologist Kenneth Oakley of the British Museum of Natural History along with biologist Joseph Weiner conducted an extensive analysis in 1953 that would reveal it as a forgery: the skull of a medieval human combined with the jaw of an orangutan, its teeth filed down and bones artificially stained to look aged. In a Science article by Michael Price, Price reports on a scientific investigation that finally pinpointed Charles Dawson as the most likely sole perpetrator of the Piltdown Man hoax. In 2009 paleoanthropologist Isabelle De Groote at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom uses these new technologies, such as DNA analysis and morphological comparison, to examine multiple specimens from both Piltdown I and Piltdown II sites and found consistent preparation techniques (staining of bones, filling of crevices with local gravel, use of dentist’s putty to re-set teeth) that all match Dawson’s known forgeries. “Piltdown Man sets a good example of the need for us to take a step back and look at the evidence for what it is,” De Groote says, “and not for whether it conforms to our preconceived ideas.”

The Piltdown case is both cautionary and fascinating because it demonstrates the susceptibility of even trained scientists to bias and nationalistic longing. Evidence was accepted because it aligned with what scientists wanted to believe: that England could claim a central role in human evolution. The eventual unmasking of the Piltdown Man underscores the necessity of maintaining skepticism, even when evidence appears to confirm cultural desires. Although Piltdown distorted evolutionary theory for decades, it allowed for other projects that led to real discoveries like Peking Man, a series of fossils classified as Homo erectus pekinensis (dating to the Middle Pleistocene era) found at the Zhoukoudian cave site near Beijing, China, now known as the Zhoukoudian Peking Man Site.

Decades later, something similar in the archaeology world took place. Shinichi Fujimura, a Japanese archaeologist nicknamed “God’s Hand,” extended Japanese prehistory far deeper than previously believed. Beginning in 1981, he “discovered” sites that seemed hundreds of thousands of years older than accepted evidence, thereby placing Japan on equal footing with continental Asia. For many Japanese academics, educators, and the general public, this was thrilling: evidence that Japan had a deep, ancient human history, on par with major continental discoveries. Museums displayed his artifacts, textbooks were rewritten, and Japan praised him for his work.

But in 2000, investigative journalists caught him on hidden cameras planting artifacts at excavation sites, revealing that more than forty sites had been falsified. The exposure devastated Japanese archaeology, forcing scholars to question the validity of dozens of sites and rewrite the national narrative from the past two decades. Fujimura himself admitted that he was under enormous pressure to produce results, but the scandal showed that his fabrications succeeded because they gave Japan the antiquity it desired, similarly to the British with the Piltdown Man. Both cases illustrate the vulnerabilities of archaeology when extraordinary claims are made without rigorous verification: when evidence aligns too neatly with nationalistic desires, skepticism often falters. In Britain, scientists wanted the “missing link” to be local; in Japan, scholars welcomed proof of an ancient heritage rivaling China or Korea. The eventual exposure of both frauds underscores how archaeology can be vulnerable to cultural bias but also how critical methodology can restore trust in the discipline. These cases show that archaeology is never isolated from politics or identity.

Kenneth Feder’s Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries emphasizes how hoaxes like Piltdown and Fujimura parallel others such as the Cardiff Giant. These fabrications succeed because they deliver precisely what audiences or nations wish to see: a rich pre-history, national prestige, or proof of legends. What these incidents reveal is that archaeology and anthropology are never just “objective” sciences; they are always embedded in cultural contexts. Hoaxes succeed because they reinforce cultural narratives and fulfill longings for certainty or national prestige. At the same time, their exposure illustrates how science can ultimately overcome deception, even if it takes decades to do so.

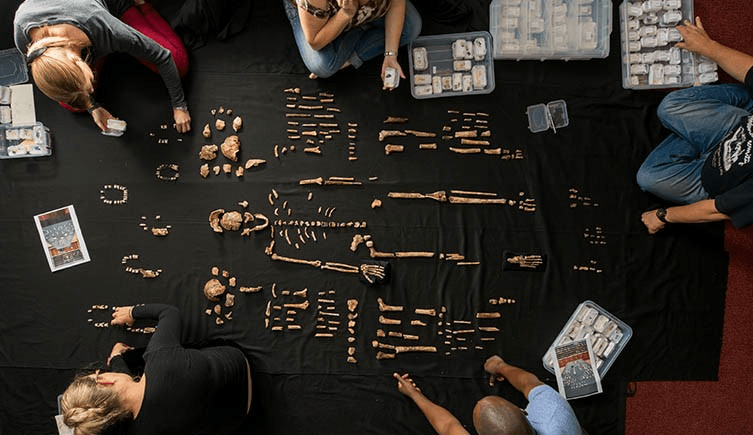

In contrast to the Piltdown and Fujimura cases, the discovery of Homo naledi in South Africa’s Rising Star Cave system demonstrates the rigor and promise of modern paleoanthropology. The name given to the species, “Naledi”, is the local name of the cave and means “star” in the local Sotho language. More than 1,400 bones representing at least 15 individuals were recovered, revealing a species with a “mosaic” of traits: small brains within the range of gorillas, upper legs and hips like ancient australopithecines, and bones of the hand, wrists, and feet that have a strikingly similar to modern humans.

In a Natural History Museum (NHM) article from 2023, author Josh David covers how recent studies claim that Homo naledi engaged in behaviors that have long been considered unique to Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, like intentional burial of the dead and symbolic engraving. Researchers base these claims on fossil remains of multiple individuals concentrated deep within the Rising Star cave system, often in chambers difficult to access, along with shallow oval depressions in sediment thought to be burial pits and stone artifacts found in close association with skeletal parts. The claims also extend to geometric engravings on cave walls near where the bodies were found, possibly marking this space as a culturally significant site. However, the article also makes clear that the evidence remains contested: many experts arguing the validity tied to Homo naledi. If accepted, these findings would push back by tens of thousands of years the earliest known intentional burials and symbolic behavior, prompting a re‐evaluation of how we define the emergence of “human behavior.”

With Homo naledi, we see archaeology at its best: careful excavation, transparent dating methods, and generous peer review. It doesn’t give us simple narratives, or center one culture or country. But it does what science is supposed to do: it gives us a more nuanced, more accurate, and often more awe-inspiring picture of human evolution. We will likely always be drawn to monsters and “missing links.” They satisfy curiosity, stir the imagination, and make us feel connected to something vast and mysterious. But when myth overtakes method and spectacle trumps evidence, the past becomes less reliable. Archaeology does more than dig bones or shard pottery; it builds narratives about who we are and where we come from. Homo naledi shows us that, even when discoveries challenge pride or expectation, real archaeology can reveal astonishing truths about our past, without fabrication.

Works Cited/References/Acknowledgements

Biodiversity Library. “Monsters, the Scientific Revolution, and Physica Curiosa.” Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog, 30 May 2013, https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2013/05/monsters-scientific-revolution-and.html

Szalay, Jessie. “The Feejee Mermaid: Early Barnum Hoax.” LiveScience, 9 Sept. 2016, https://www.livescience.com/56037-feejee-mermaid.html

Harvard University. Harvard’s FeeJee Mermaid. YouTube, 30 Oct. 2017, youtu.be/MeK40LXEIO4

Natural History Museum, London. “Piltdown Man.” Library & Archives Collections, The Natural History Museum, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/services/library/collections/piltdown-man.html

“Study Reveals Culprit Behind Piltdown Man, One of Science’s Most Famous Hoaxes.” Science, 2016, https://www.science.org/content/article/study-reveals-culprit-behind-piltdown-man-one-science-s-most-famous-hoaxes

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian.” World Heritage Centre, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/449/

Feder, Kenneth L. “Anatomy of an Archaeological Hoax.” and “Dawson’s Dawn Man,” Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. 8th ed., Oxford University Press, 2013

“Natural History Museum, London.” Claims that Homo naledi buried their dead could alter our understanding of human evolution, 14 June 2023, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/june/claims-homo-naledi-buried-their-dead-alter-our-understanding-human-evolution.html

National Geographic. New Human Ancestor Discovered: Homo naledi. YouTube, 10 Sept. 2015, youtu.be/oxgnlSbYLSc?si=l6FjQsxf61Qj2GKl.

Leave a comment